This is the first in a new series called Vector Technical, which you'll be able to access in the category filter of the Vector Online landing page.

A TAIC report1 into a 2023 vortex ring state accident said it was critical that helicopter pilots know the warning signs of VRS – the suddenly unstable air that can kill.

The Transport Accident Investigation Commission found the primary focus of the EMS pilot had been outside the aircraft on a patient’s location. His instrument scan was therefore reduced and he didn’t recognise in time that the helicopter’s forward speed and descent rate were favourable to vortex ring state.

TAIC noted that such a lack of situational awareness means pilots fail to recognise their aircraft is in trouble until it’s too late to recover.

What is VRS?

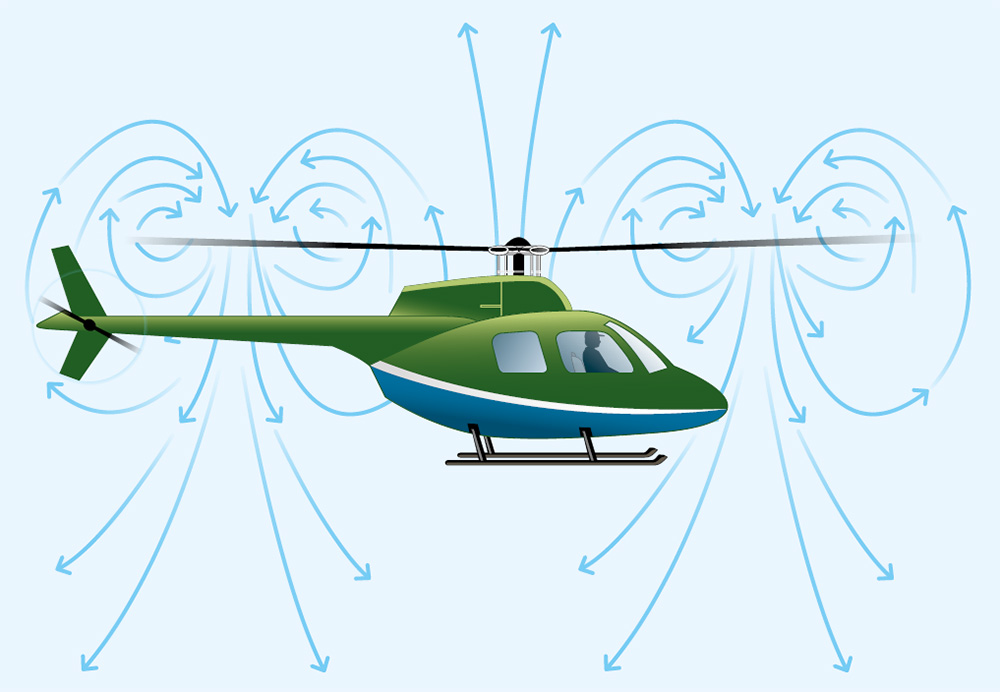

Vortex ring state occurs when, at certain descent rates and low forward air speeds, the wake of the helicopter's main rotor becomes unstable and collapses, engulfing the rotor in a ring-shaped, recirculatory flow.

It’s most at risk of happening during downwind approaches.

The condition can be sudden, and it results in a rapid increase in rate of descent. Any increase in rotor thrust to reduce this, further energises the vortices and increases the rate of descent.

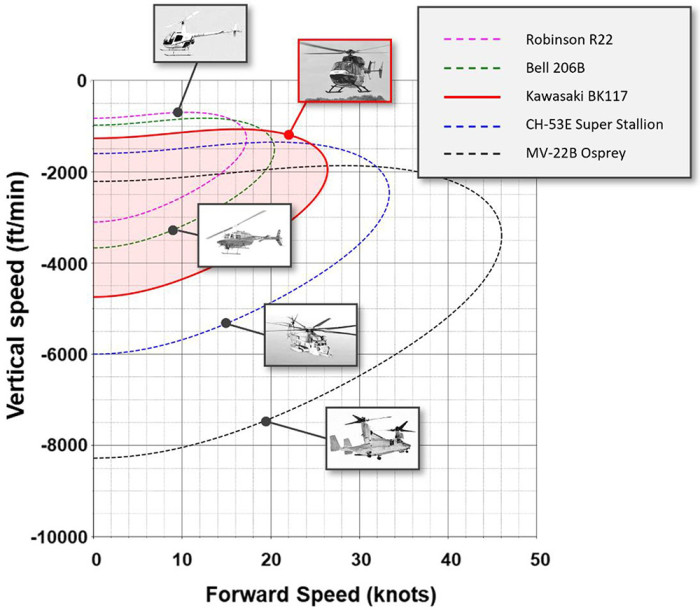

Predicted VRS onset boundaries for various conventional helicopters. Source: Dr Richard E. Brown, Sophrodyne Aerospace/TAIC report AO 2023-010.

The influence of wind

TAIC’s 2025 report into the VRS accident found that the pilot hadn’t taken into account the effect of the orographic winds2 across the ridge along which the helicopter was flying.

Jason Frost-Evans, CAA Investigator and 4,500-hr rotary pilot (including EMS) says a moderate updraught of 300 to 800 feet a minute can lead to vortex ring state in straight and level flight.

“An updraught in the mountains has the same effect on the helicopter as if you have a higher rate of descent.

“The rotor system doesn’t recognise whether it’s going down, or the air is coming up. It’s the same thing. And I’m not sure if that is well understood.

“You need to be cognisant of vertical air movement. Just looking at your vertical speed indicator isn’t necessarily enough for more advanced operations.”

Recognising the signs

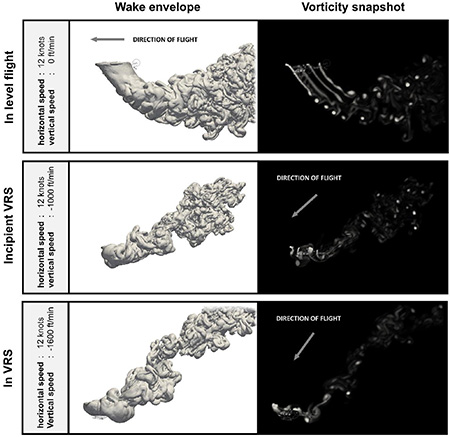

Structure of the rotor wake in level flight compared with the structure in fully developed VRS. Source: Dr Richard E Brown, Sophrodyne Aerospace/TAIC report AO 2023-010. View larger image [JPG, 378KB].

Allan Menard, CAA Manager of Engagement and Interventions, is a 10,000-hr rotary training pilot who’s been instructing VRS recovery techniques for 20 years.

He says the first sign of entry into vortex ring state is a sudden uncommanded descent.

“As the turbulent airflow from the main rotor interferes with the tail rotor’s inflow, erratic yaw inputs follow.

“It may feel like the transition from forward flight to a hover, so if you’re not situationally aware, you may miss it.

“It may feel like the pedals are unresponsive, but what’s really happening is the tail rotor is essentially trying to bite into a swirling mess of vortices, which can vary moment to moment. The nose may become ‘twitchy’.

“The tail rotor thrust is degraded, becoming unsteady and asymmetric, due to the chaotic airflow environment.

“Then, as you fall into VRS, you feel as if your seat is falling away from your body, a little like on a roller coaster ride.

“After that, the aircraft’s movement can actually feel quite smooth – it’s just that now you’re descending very quickly, 750 or 1000 feet per minute, or greater.”

Allan says the instinct to raise the collective, as the ground fast approaches, only makes the situation worse.

“So it’s critical for pilots to be aware of what’s occurring, what they’re in, and what they have to do to get out.”

On avoiding VRS

To describe avoiding VRS, CAA Flight Examiner (H) Andy McKay, uses the analogy of a car sliding out on a corner.

“As helicopter pilots, we must be looking ahead to the ‘corner’, assessing conditions for the likelihood of VRS, and taking the necessary avoiding manoeuvres before it develops,” he says.

“The path from incipient to fully developed VRS can be measured in seconds — recovery margins are slim.

“Like a car sliding out in a corner, by the time VRS takes hold, it’s often too late. The skill lies in anticipating the corner, not reacting to the skid.

“Recognition and avoidance remain the most effective tools against vortex ring state.”

Jason Frost-Evans says that following basic professional flying techniques, which should be baked into a pilot’s training from day one, can make them as safe as possible.

“Firstly, airspeed is critical, and you should be alert for other VRS factors when you reduce it on an approach. Secondly, default to approaching into the wind and plan carefully if there’s a good reason not to.

“And finally, fly a stabilised approach avoiding large power changes or aggressive manoeuvring, especially at low airspeed.

“That’s your starting point. Flying professionally and complying with these fundamentals will keep you safe most of the time.”

For CAA Aviation Safety Advisor Pete Gordon (and a 10,500-hour rotary pilot) avoiding VRS starts at preflight stage.

“You’re considering the weather and the terrain – and whether the combination of both is likely to cause VRS.

“Then you remain vigilant to the possibility of VRS as you carry out the job, so you’re not caught unawares if – or when – it happens.”

The challenges in VRS training

A gap in the flight manuals

TAIC found that the flight manuals of many helicopter types don’t contain the necessary information for pilots to identify the flight conditions and parameters for the helicopter type, that are conducive to VRS3. This is why, it concluded, pilots commonly rely on rules of thumb to avoid and deal with VRS.

The problem with using such a ‘probably good enough’ approach is that, as TAIC noted, the rule of thumb used by the pilot in the 2023 accident, “…made no allowance for the type of helicopter that they were flying, nor for the actual disc loading of the rotor … nor for how the helicopter's pitch attitude might have been conducive to earlier-than-anticipated VRS onset”.

A gap in the training

Apart from some generic training in identifying and getting out of VRS, it isn’t taught sufficiently, or sufficiently well. This is according to Claude Vuichard, the Swiss flight examiner behind the Vuichard Recovery (from VRS) Technique.

“More important than learning how to recover from VRS, is to learn to recognise and avoid it in the first place,” Claude says.

“But many instructors – especially low-hour instructors – are, themselves, uncomfortable with intentionally putting the aircraft into VRS during training. It’s a special flight phase, and they’re not confident to enter it. This means many student pilots don’t learn to recognise the initial signs.”

The load on the aircraft

The operator of the downed helicopter told TAIC that VRS was integrated into its training syllabus, with emphasis on recognition and avoidance.

However, practising recovery from VRS stopped after Airbus Helicopters published a safety information notice4 “…recommending that operators do not intentionally place the helicopter in fully developed VRS because of the aerodynamic loads imposed on the helicopter”.

Allan Menard says while the Airbus safety notice does “provide a limiting condition”, there are other aircraft that pilots can fly to learn how to identify incipient VRS.

And he says some training in the air is essential because, “While it can be introduced in the classroom, recognising VRS is not something that can be totally taught on the ground”.

Training in VRS cues

“Pilots are pretty tactile learners,” says Allan. "They have to see what’s going on with their own eyes, and feel with their hands and feet.

“And training in the air can be done safely if it’s done several thousand feet AGL.”

“If you lose height during the manoeuvre, or it goes wrong, there’s plenty of sky to recover.”

Allan also recommends check and training pilots talk about VRS as much as possible – even when doing other training.

“For example, if a student pilot is doing a reconnaissance and they have to descend a slope to land in a confined area, the instructor can be reminding them that this is exactly how you can get into VRS, if you’re task-saturated, and not paying attention.

“Talking about it as much as possible, repeatedly reminds the student of the conditions conducive to VRS.”

Jason Frost-Evans says identifying and recovering from VRS is also set out in the demonstration of competency for type ratings in Advisory Circular AC 61-10 Pilot Licences and Ratings – Type Ratings.

“There are differences between individual helicopters. A helicopter with higher disc loading is generally prone to entering vortex ring state (VRS) at a higher airspeed and rate of descent than one with lower disc loading.

“Not only should the surrounding flying environment be taken into account, so should the characteristics of the aircraft being flown.”

Planning for VRS

A BK117 / H145 rescue helicopter on its way to the driver of a vehicle which left the road and fell down a steep bush-covered hill in Christchurch in 2020. Photo: Alamy/Hugh Mitton.

Pete Gordon has supervised new-to-country helicopter pilots to be VRS-aware, particularly in the mountains of Papua New Guinea, where he flew, mainly external load and drill shifting, for nearly five years.

“If you’re going to be operating low-level, with very little opportunity or buffer to recover, and you haven’t planned properly and you have poor handling technique, then it’s going to be trees, rocks, and various other bits entering the cockpit area.”

Pete says it’s imperative, therefore, that a pilot understands the job, and plans accordingly.

“It’s about recognising there’s a high potential you could enter VRS doing this job. So how are you going to mitigate that?

“Often, it’s just giving yourself a bit more space – particularly in mountainous country or on steep slopes – so you give yourself an escape route.

“The worst scenario is that you’re putting a load onto a pad, while facing the hill.

“That gives you so few options – or none – that you’d be absolutely lucky to get away with it.

“Whereas, putting the load down with a slow descent rate and the aircraft aligned parallel with the hill face, gives you options to peel off into a valley or move the aircraft rotor system into clean (undisturbed) air.”

Tips from the logging pilots

Pete says logging pilots are particularly mindful of VRS, because they’re flying in challenging terrain where, typically, they’re picking up a log then setting it on to a handling pad, for further processing.

“That handling pad is generally below where they’re picking up the logs from. So they’re going to be descending, with slowing forward speeds, and in and out of wind – including possible wind from the tail.

“So they’re setting themselves up to be very likely to enter VRS.”

Pete says it’s something experienced long-line pilots think about, anticipate, and plan for, constantly.

“You don’t have to enter VRS too often to understand the devastating effects it can have.

“Even if they go to a new position or a new logging block, a pilot will look at the terrain, and they’ll look at where the log pile is going to be. And probably the very first thing that’s going through their minds is the possibility of VRS. It’s seared into their brains before the machine is even flown.”

Pete says it’s important pilots learn how the machine feels just as it’s entering VRS.

“You get to know how the cyclic feels and what the aircraft vibrations mean. And the instant one or two of those warning signs occur, you do something about it. You don’t sit there and wonder what’s going on.”

Pete says logging pilots can recognise incipient VRS many times during a single day of logging.

“But they’re very experienced at not letting this situation develop, so yeah, it’s almost part of the job really. It’s just reminding them they could be doing the job better.

“Someone who’s learned to recognise the signs; who’s planned the job; who remains situationally aware; and who’s also experienced in recovering from it, will not find entry into VRS too big a deal.

“But someone who’s done none of those things may well end up having a very bad day.”

Have a Plan B (like always)

Jason Frost-Evans has, himself, tangled briefly with VRS, and he remembers it as a situation that, “…certainly got my attention”.

He says there’ll be some environmental situations so challenging that the pilot may just have to postpone the job.

“Sometimes you just can’t land safely in the place you want to with a particular helicopter and configuration, because of the combination of conditions, terrain, obstacles, and aircraft performance.

“There may be something you can change to make it work, but sometimes, you just have to have a Plan B or leave the job to another day.”

Now read . . .

GAP Booklet: Helicopter performance [PDF 3.1 MB]

Footnotes

1 TAIC report AO 2023-010(external link)

2 A mass of air lifted by a geographical feature such as a line of hills or a mountain range. See skybrary.aero/articles/orographic-wind(external link)

3 Since the accident, Kawasaki has revised the flight manual of the accident aircraft type – BK117 – giving more information about how to recognise and avoid VRS.

4 No. 3463-S-00 (Airbus, 2022).

Main photo: aerialstage.com/valair.ch/Vuichard Recovery Aviation Safety Foundation