Understanding the weather between your departure and destination points is an important step in your flight planning.

In 2018, an Alpi Aviation Srl Pioneer 300 crashed in the Taringatura Hills in Southland, after entering fog at low level. The accident was established as controlled flight into terrain (CFIT).

In 2019, a Tecnam P2002 Sierra RG also had a CFIT accident, in the lee side of the Tararua Range, after being caught in downdraughts.

The original plan was to operate Paraparaumu to Foxpine, but at some point the crew made an inflight decision to fly to Flat Point on the east coast.

They had only the Straits area forecast package, which indicated strong north-westerly winds of 20-30 knots above 1000 feet, and the NZ Graphical SIGMET Monitor diagram, which indicated turbulence in the Wairarapa.

The report noted it was a sunny day in the Wairarapa and that the crew would probably be able to see through the Tararua Range beneath the cloud base.

Unfortunately, one of the causes of this accident were that the crew didn’t appear to consider the significance of the conditions in the lee of the Tararua Range, given the forecast winds’ velocity that day. Nor did they obtain the latest available weather information for the new route. Even if the weather appears ideal at both your departure and destination points, it’s vital that you know what to expect in between.

In this article, CAA Chief Meteorological Officer Paula Acethorp, MetService Meteorologist Ashlee Parkes, CAA Safety Investigator Peter Stevenson-Wright, and a regulatory investigator, Jason Frost-Evans, provide some insights.

We’ll also look at one of the newer certificated tools to help you plan safe and enjoyable flights.

The value of weather experts

Checking the weather is part of thorough preflight planning. Here, Wellington Aero Club’s Pete Mitchell literally maps out a flight from the capital to St Arnaud and Nelson.

“I was taught early on in my cross-country training to spend the same time on preflight planning as I expected to be in the air. I’ve since become more efficient, but I still always set aside a fair amount of time on the ground, to reduce workload and surprises in the air!”

MetService Meteorologist Ashlee Parkes explains why their advice is the best.

“Meteorologists who work in the aviation section at MetService are tested every three years to ensure they are competent with the products and workflow, given the safety-critical nature of aviation forecasting. A high-level technical understanding of the atmosphere, climate, and weather models is required.”

It’s clear that creating accurate forecasts for New Zealand’s aviation community is no small task. Ashlee describes the weather models she uses in her job, and how they work.

“At MetService we use three global weather models. We take these and run models of a high resolution, 8km and 4km, across Aotearoa New Zealand.

“Unfortunately, these models don’t perfectly represent reality, and this difference is most apparent across Aotearoa’s mountainous regions.

“The weather is heavily influenced by the local terrain. Winds channel through valleys, fog forms more regularly in basins, and the uplift of air over mountains causes cloud formation.

“If the models can’t perfectly represent the mountainous geography of the land, how do we expect them to perfectly predict the weather?

“This is where having a qualified meteorologist analyse the models shines. We analyse the models, compare them with real-time observations, and use our knowledge about the terrain and local effects to compile a forecast.”

Paula Acethorp agrees. “MetService’s Graphical New Zealand Significant Weather (represented in MET documents as ‘GNZSIGWX’) and Graphical Aviation Forecast (GRAFOR) charts are the only aviation-specific products giving you the expected en-route conditions in New Zealand, to support effective preflight planning.”

Jason Frost-Evans says there are “plenty of colourful apps and platforms which are a great indication of the risk of your washing not drying.

“But don’t trust them to indicate the ceiling, inflight visibility, or conditions that are hazardous to aviation, such as icing or hail.

“They’re just not designed for that purpose.”

PreFlight – the weather app doing it all

While there are plenty of free weather apps out there, using a Part 174-certificated supplier gives pilots the assurance that a qualified meteorologist has produced the forecast, and that the underlying systems are supported by a safety management system.

PreFlight provides the same aeronautical information you’d find on a VNC, along with meteorological information, airspace advisories, briefings, and aerodrome information, including NOTAMs.

“It’s never been easier to check NOTAMs or get the latest weather,” says Safety Investigator Peter Stevenson- Wright, “as well as review a lot of other information before you get in an aircraft.

“As a safety investigator of more than 20 years, I hope I’ll never see another occurrence involving a pilot not checking the weather, or their NOTAMs, before a flight.

“PreFlight makes it easier to satisfy the requirements of rule 91.217 Preflight action.

“Pilots, ask yourself this,” questions Peter. “‘Is my life worth 180 seconds?’ That’s about how long it takes to select and request weather information and NOTAMs in PreFlight.”

Paula agrees. “Rule 91.301 VFR meteorological minima tasks pilots with making sure VFR minima can be complied with along the route. But most model-based weather apps can’t provide cloud base or visibility forecasts.

“The GNZSIGWX and GRAFOR charts are both available to pilots through the PreFlight website. In fact, PreFlight is free for recreational pilots – so there’s no reason for them to not have all the right information.

“Pilots should also familiarise themselves with the times forecasts are issued, so they can make sure they have the most up-to-date information before take-off.

“Some local-scale weather is a bit trickier to forecast, and it’s often not until a day out that it becomes clear that thunderstorms are likely that afternoon, or fog will form that night.”

“If you find that the conditions aren’t what you expected,” says Jason, “then don’t forget that FISCOM (flight information service communication) is available in most places, or you can talk to ATC. Ask them for the latest report for your destination or nearby airports, and consider making a PIREP (pilot report) so other pilots are aware.

“Remember, if the weather has an impact on the safety of the operation, you should file a 005 report, especially if MET minima are breached.

“That way, if there are trends, the CAA and MetService can work together to improve the service.”

Just wing it? Yeah, nah

The CAA says the days of ‘winging it’ are gone. We now have readily available resources to ensure that weather doesn’t ruin your flight. Your passengers and family will expect you to keep yourself and anyone in your care safe, so be professional, and use the best and most appropriate resources available for every flight you’re planning.

Decoding the GRAFOR

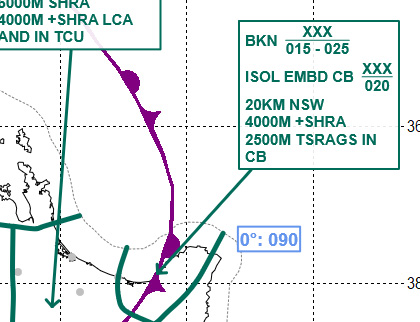

What are the meteorologists telling you here? It’s worth reminding yourself that this is a snapshot in time, with validity +-3hrs, so that’s potentially a lot of information to convey!

Let’s focus on the eastern Bay of Plenty – and firstly, look at the cloud group. The meteorologist is expecting prevailing cloud conditions of broken cloud (5-7 eighths of the sky covered), with bases between 1500ft to 2500ft above mean sea level.

Source: MetService

The tops of those clouds are above the vertical limit covered by the GRAFOR – extending to at least 10,000ft and depicted by XXX. Separate to that cloud, there will be isolated cumulonimbus (CB) clouds, with a base of around 2000ft, tops beyond 10,000ft.

The next few lines describe the weather that can be expected. ‘NSW’ means ‘nil significant weather’, so mostly there won’t be any weather of concern.

But as the front passes through that region, the weather is expected to deteriorate for a time with heavy showers of rain (+SHRA). This will reduce the visibility to 4000m, and with those isolated CB connected to the front, the visibility could reduce further to 2500m in thunderstorms, rain and small hail (TSRAGS).

The TAF (terminal aerodrome forecast) equivalent would be a ‘TEMPO’ of poorer weather for a time with the passage of the front. In this example, it would be a good idea to also check the Whakatane TAF to get a feeling for the speed of the passage of the front through the region, along with any observation that might be available.