A CAA investigation into a March 2025 fatal accident has highlighted the critical need to position safely, before trying to turn in a valley.

It was early afternoon on a beautiful, blue sky autumn day in the Otago valley of Dingle Burn, when a Piper Pacer, with two on board, crashed into sloping ground.

The passenger died at the scene, and the pilot was airlifted to hospital, where he was placed in a coma for 10 days, before making a slow recovery.

The investigation found the pilot had begun a turn in a valley with insufficient horizontal space to complete that turn. The aircraft was flying at very low level and very slow speed during the attempted turn, and it stalled, at too low a height to recover.

Because the pilot has no memory of the accident, the investigators have had to surmise what happened. They believe the pilot began the turn from that position because he was confused by reduced visual cues in the confined valley environment and he couldn’t accurately perceive the horizon.

Leading up to the accident

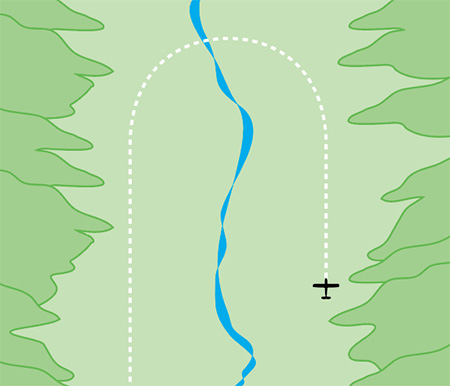

Flying to one side of the valley with escape option available and checking that more terrain is showing behind the pass ahead. The escape option to the right is better. Source: Mountain flying Good Aviation Practice booklet.

The pilot and his passenger had been part of a two-day NZAOPA (Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association) fly-in, to experience flying in remote and mountainous areas, as well as in and out of remote airstrips.

The pilot, part of a group of 11, had already landed at and departed two rural airstrips, and was now entering the head of the Dingle Burn valley, tracking south and passing abeam a third rural airstrip, where other aircraft had already landed.

The pilots already on the ground saw the aircraft go around at the airstrip, and fly back up the valley. (The pilot, post-accident, had no memory of why he’d chosen to go around).

When the aircraft didn’t return, the other pilots became concerned, and one of them took off to try to find it. He quickly found the crashed Piper Pacer, just over a kilometre from the airstrip.

Investigators found the damage to the aircraft was consistent with it impacting the ground with a low forward speed but a high rate of descent. The cockpit and cabin structure was significantly compressed. The damage to the propeller and its attachment bolts indicated the engine was producing high power/rpm at the time of the initial impact.

How it happened

The investigation found that 51 seconds after the go-around, the pilot had positioned the aircraft towards the eastern or left side of the valley. He began a right turn through approximately 70 degrees, at an angle of bank of approximately 35 degrees, in an attempt to return to the airstrip.

Halfway through this turn, the aircraft’s groundspeed decayed to 51 kts while it was approximately 69 ft above the ground. One second later the aircraft reached its maximum height since the go-around, of approximately 78 ft above the ground, but the ground speed had reduced to 45 kts.

Approximately halfway through the right turn, the aircraft stalled aerodynamically and departed from controlled flight.

The aircraft impacted terrain with an average rate of descent of 936 feet per minute and a groundspeed of 41 kts.

Positioning to one side of the valley leaves maximum room to turn. Always use the maximum room available in case a 360-degree holding turn is required.

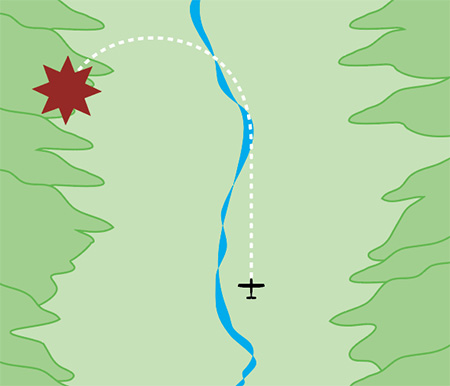

Positioning in the middle of the valley means a steeper turn is necessary and there may be insufficient room to turn back safely. Source: Mountain flying.

The lessons to learn

“Had the aircraft remained on the western side of the valley while continuing to climb,” says CAA Investigator Roger Shepherd, “the likely additional horizontal space would have allowed the aircraft to change direction safely.”

Roger says if you’re flying in a valley, and need to complete a 180-degee turn, you should position your aircraft as high as possible to one side of the valley.

“You then carry out the turn toward the opposite side of the valley, with the angle of bank being adjusted, during the turn, to be no steeper than what’s needed to complete the reversal of direction.

“Leaving the maximum room to turn also means less bank angle is needed, therefore less wing loading, a lower stall speed, and less pressure on the pilot.”

The role of horizon

Dead-end valley. Source: Mountain flying.

“When surrounded by mountainous terrain there won’t be a representative view of the horizon,” says Roger. “The pilot will have to imagine where the true horizon lies and select the appropriate nose attitude accordingly.

“The lower the aircraft is, relative to the terrain, the harder it is to establish the correct horizon. The effect may be worse in a climb due to the limited forward view.

“As the aircraft approaches higher terrain, the horizon can appear to be moving up the windscreen and this effect is more pronounced the closer the aircraft is to terrain.

“In response, a pilot may subconsciously apply back pressure on the elevator control to keep the horizon in the normal place. If unchecked, this will result in a loss of airspeed and an aerodynamic stall.

“As the pilot began the right turn toward the eastern side of the valley, his view ahead would have rapidly become one of a close and steep mountainside with the skyline over 30 degrees above the true horizon.”

Roger says that identifying a useable horizon is not an innate ability but a skill that must be learned. Without such a skill, he says, it’s difficult to maintain a consistent nose attitude, manoeuvring in a valley could be hazardous, and safety margins are therefore eroded.

“You need 5 to 7.5 seconds to see, evaluate, decide and execute. If you’re in sink and at low level, this time plus any time taken to move over in the valley, will be longer than you have.

“In narrow valleys, commit to one side or the other, preferably the right-hand side. Under no circumstances – except perhaps in a very wide valley – position yourself in the middle of the valley.

“The message is a simple one,” says Roger. “Never place the aircraft in a situation where there’s insufficient room to turn back safely.”

And now . . .

GAP booklet: Mountain flying [PDF 1.5 MB]

Read the full report: ZK-PEE Investigation final report [PDF 1.4 MB]

Footnote

Main photo courtesy of Aaron Pearce.